What’s in a name?

With Mammal March Madness happening this month, I’ve been seeing a lot of common names for mammalian species in my Twitter feed and this year in particular two of the divisions are based directly on common names: Adjective mammals (e.g. Spectacled bear, pouched rat, clouded leopard, etc. ) and Two Animals One Mammal (e.g. bearcat, tiger quoll, hog badger, etc.). I recently had to figure out how to do text analysis for another project (in which I counted the most frequently-used words in the titles of hundreds of papers), so I wondered if I could apply the same analysis code to the common names for mammals (turns out I could). This post has two parts: Part One is a straightforward text analysis of word frequency, and Part Two is a nifty approach to quantifying name lengths.

Part 1: What are the most frequent words in the common names of thousands of mammalian species?

I’m doing this post for common names in English because these made for the largest dataset. Personally, I rarely use common names and we don’t really have nearly as many in Spanish - although some of the ones we have are pretty cool (e.g. tlacuachín, chungungo, and viejo de monte).

For this post we’ll use the tidytext R package and a massive list of common names for mammals that’s available thanks to the IUCN Red List assessments. All the code here should be fully reproducible, although you will probably need to install various packages first.

# load libraries

library(dplyr)

library(tidytext)

library(ggplot2)

library(forcats)

library(hrbrthemes)

library(ggalt)

library(extrafont)

## IUCN Red List data (download and tidy-up)

IUCN <- read.csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/ManuelaGonzalez/Who-is-Who/master/Mammals_2017_01_05.csv", stringsAsFactors=FALSE,strip.white=TRUE)

commNamesTax <- IUCN %>% select(Order,common_name=Common.names..Eng.,Genus,Species) %>% mutate(scName=paste(Genus,Species,sep=" "))Once we download the IUCN data that we had from another post we use unnest_tokens() to split up the common names and end up with a row for every token (in this case words). With the words in this long format, we can easily quantify them using count(). Pretty cool and pretty simple.

## for all species

# saves entire title in `title_all` column

# splits up title column creating the `word` column -

# with a row for every token (word)

namesAll <- commNamesTax %>% mutate(names_all = common_name) %>% unnest_tokens(word, common_name)

# no need to remove stop words here

# quantify

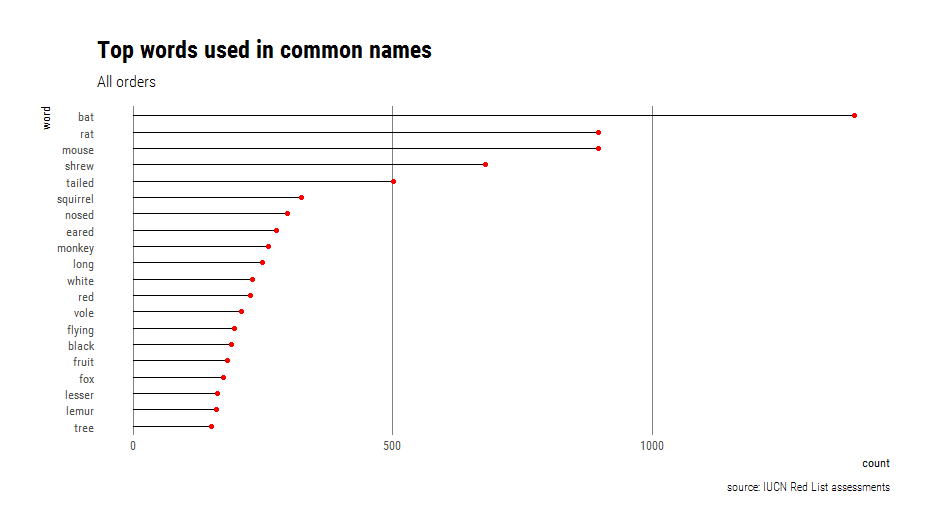

by_wordAll <- namesAll %>% count(word, sort = TRUE)I chose an arbitrary number of 20 top words to plot, using ggalt and hrbrthemes to make crisp and minimalist lollipop charts.

# prepare for plotting

loadfonts(device="win")

# plot

by_wordAll %>%

top_n(20) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = fct_reorder(word, n), y = n)) +

geom_lollipop(point.colour = "red",horizontal = F) +

coord_flip() +

labs(title = 'Top words used in common names',

subtitle="All orders",

caption="source: IUCN Red List assessments", x="word",y="count") +

theme_ipsum_rc(grid="X")Unsurprisingly, the top words for all orders reflect the names of the most diverse groups (rodents, bats, shrews and primates)

To gain more insight, we can join the list of top words with the Parts of speech data frame that comes with tidytext. This dataset contains hundreds of thousands of English words from the Moby Project by Grady Ward, with each one tagged as “Noun”, “Adverb”, “Adjective”, or “Verb”, among other options. For some of the top terms there were multiple matches (for example: “flying” as an adjective, a noun, and a verb) but we can keep the first match using slice(). I also fixed up missing or mismatched terms manually using case_when().

I wrote a function to get the top n words, mainly as a way to document how non-standard evaluation works for unnest_tokens_ because I couldn’t find anything in the help files. Hint: it takes the arguments as character vectors.

# function to get top n

get_top_n_words <- function(x,y,n){

allwords <- x %>% unnest_tokens_(c("word"),c(y))

wordcount <- allwords %>% count(word,sort=TRUE)

topwords <- wordcount %>% top_n(n)

return(topwords)

}

# get top 20 words and tag them

topWspeech <- get_top_n_words(commNamesTax,"common_name",20) %>% left_join(parts_of_speech)

# slice because of multiple matches

twspeechSliced <- topWspeech %>% group_by(word) %>% slice(1)

# fix missing or mismatched words manually

twspeechSliced <- twspeechSliced %>% ungroup %>% mutate(wordType= case_when(

.$word=="tailed"~"Adjective",

.$word=="nosed"~"Adjective",

TRUE~ .$pos))

twspeechSliced %>% count(wordType) %>% mutate(wtypePercent= round(nn / sum(nn),2))Among the top 20 words and ordered by frequency:

- Nouns outnumbered adjectives (55 vs 45%).

- Tails, noses, and ears are the most common features used to describe species.

- White, red, and black are the most common colors used to describe species.

- Long, flying, and lesser are the most common descriptors of different attributes or animals.

Even when expanding to the top 50 words, people’s last names did not make it into the list and the only place name is “African” at number 41. I kept looking and “Thomas’s” appears in a 10-way tie at number 125, with 33 species that include “Thomas’s” in their common name (e.g. Thomas’s Shrew Tenrec Microgale thomasi and Thomas’s Giant Deer Mouse Megadontomys thomasi). This is mainly because so many species have been named in dedication to British zoologist Oldfield Thomas.

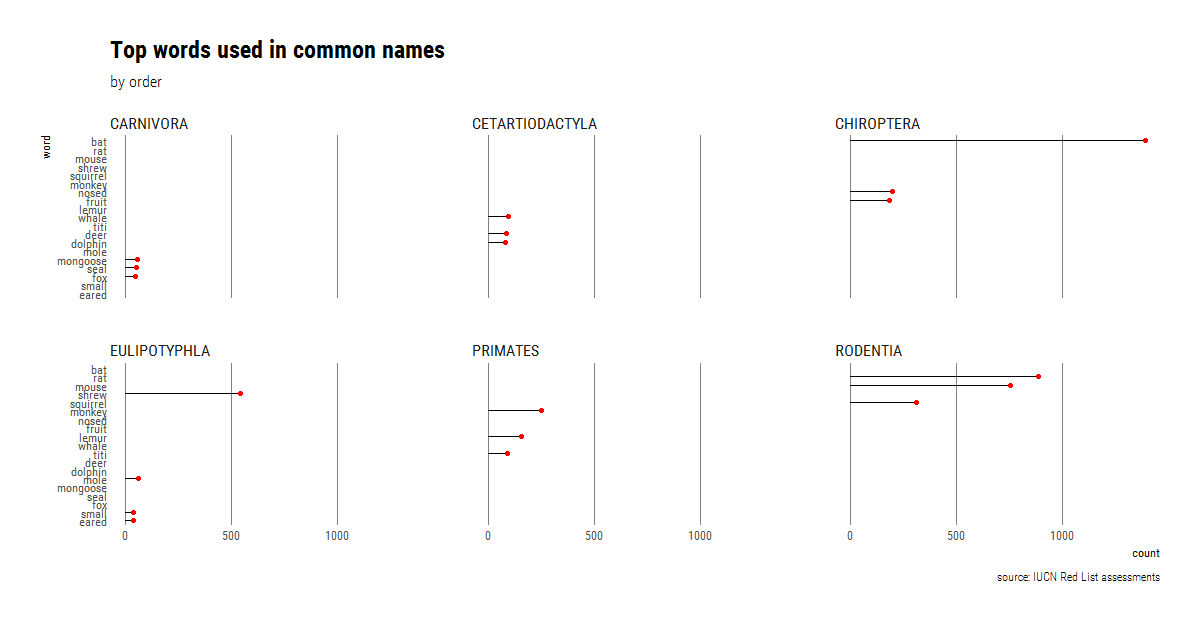

We can then use faceting to repeat the plot for the six most speciose orders (>150 species) but with way less top words (for visibility).

# to redo by order

# work only with speciose orders (more than 150 species)

# group and subset the data

commNames_speciose <- commNamesTax %>% group_by(Order) %>% filter(n() >= 150)

# get top three words

topWbyOrder <- get_top_n_words(commNames_speciose,"common_name",3)

# plot with facetting

ggplot(topWbyOrder,aes(x = fct_reorder(word, n), y = n)) +

geom_lollipop(point.colour = "red",horizontal = F) +

coord_flip() +

labs(title = 'Top words used in common names',

subtitle="by order",

caption="source: IUCN Red List assessments", x="word",y="count") +

theme_ipsum_rc(grid="X")+

facet_wrap(~Order)

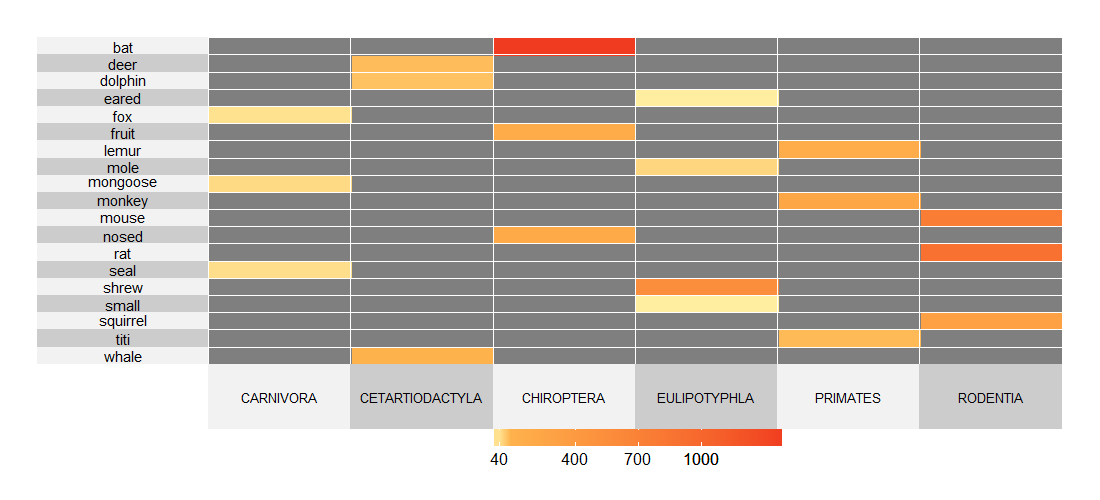

We see that there is essentially no overlap in the most frequent words, but this is probably not the best way to visualize the high amount of mismatch. Instead, we can condense way more information using a heatmap, in this case created using Rebecca Barter’s superheat package. To make the heatmap, we take advantage of dplyr’s grouping capabilities before running the function to get the top n words. Afterwards all we need to do is change the data from long to wide format (using tidyr::spread in the same way we would have used reshape2::cast), and wrangle the row names into the order we want to use.

# change from long to wide format

library(tidyr)

topWbyOrderLong <- topWbyOrder %>% spread(Order,n)

# for heatmap

devtools::install_github("rlbarter/superheat")

library(superheat)

# wrangle row names

# this is because of the implicit sorting in tidyr

topWbyOrderLong <- as.data.frame(topWbyOrderLong)

topWbyOrderLong <- arrange(topWbyOrderLong,desc(word))

row.names(topWbyOrderLong) <- topWbyOrderLong$word

topWbyOrderLong$word <- NULL

# create heatmap

superheat(topWbyOrderLong,heat.col.scheme = "red",

left.label.text.size = 4,

bottom.label.text.size = 3.5,

grid.hline.col = "white",

grid.vline.col = "white")The heatmap shows how there are no shared top words between the six most diverse orders, and also the frequency of each one.

Finally, I wrote a very crude function to generate new common names by just mashing up some of the popular words following three few simple formulas (adjective adjective noun, noun noun, adjective nounnoun).

# function to mash up common names

# inputs are:

# dat: a datafame with a 'word' column

## howmany: how many sets of common names to produce

newMammal <- function(dat,howmany){

datSpeech <- dat %>% left_join(parts_of_speech) %>%

group_by(word) %>% slice(1) %>%

na.omit()

adjs <- datSpeech %>% filter(pos=="Adjective")

nouns <- datSpeech %>% filter(pos=="Noun")

newMammA<- list()

for (i in 1:howmany){

newMammA[[i]] <- paste(sample(adjs$word,1,replace = F),sample(adjs$word,1,replace = F),sample(nouns$word,1,replace = F))

}

newMammB<- list()

for (i in 1:howmany){

newMammB[[i]] <- paste(sample(nouns$word,1,replace = F),sample(nouns$word,1,replace = F))

}

newMammC<- list()

for (i in 1:howmany){

newMammC[[i]] <- paste(sample(adjs$word,1,replace = F)," ",sample(nouns$word,1,replace = F),sample(nouns$word,1,replace = F),sep="")

}

newMamms <- c(newMammA,newMammB,newMammC)

newMammsVecDF <- newMamms %>% simplify2array() %>% sample() %>% data.frame

return(newMammsVecDF)

}

# try it out

newMammal(by_wordAll,10)Most of the output makes no sense, but there were some funny ones, and I decided to draw a few with my epic MS Paint skills. Below is a sample of 100.

This function could be vastly improved by using more tags other than noun and adjective. For example, it’s possible to follow this post by Maëlle Salmon to separate animal names from other nouns.

100 random mashed up names

1 soricine dayakmar

2 pardine vampire

3 canarian lar

4 imposter dormouse

5 grizzled nepalese wisent

6 round birdlike graybeard

7 tumultuous hairless cochabamba

8 mesopotamian turkish capybara

9 bramble nyala

10 clara limestone

11 disk herring

12 sugar gazelle

13 margareta mashona

14 scaled basilanoubangui

15 siberian apevincent

16 sprightly unadorned bolo

17 cuban red ounce

18 hipped banded crescent

19 bidentate muleisland

20 wombat ringtail

21 toad niger

22 lipped herringnyala

23 limestone nonsense

24 himalayan gray saki

25 australasian tuftguadalcanal

26 riparian principal bobcat

27 lipped legged shadow

28 snouted zuluqueen

29 rough tubechipmunk

30 roan cottontailduiker

31 nimble black thomas

32 handed mountainkey

33 algerian colombian gold

34 rhino chad

35 naked equatorial podolsk

36 korean aurochsfur

37 thicket runner

38 prehensile bannershansi

39 gobi shark

40 colorful furred chiru

41 killer shadow

42 delectable mesquitelion

43 polynesian tamarmonk

44 colorado ethiopian bini

45 alexandrian shrewlike jones

46 caspian lorisvalais

47 rusty humpbacked humpback

48 dramatic sachathailand

49 larger ayecyrenaica

50 finless colorful langur

51 typical vietnammullah

52 squirrel jerboa

53 bush stick

54 woolly stony nord

55 wolf weasel

56 ibex markhor

57 pampas el

58 antarctic indochinese gervais

59 slaty proboscisdiadem

60 fur forest

61 mayan chacmasound

62 siam montague

63 swift destructive ebony

64 pallid baptistachannel

65 subalpine noble timor

66 river granada

67 micronesian rough runner

68 flores john

69 colored hispid st

70 pipistrelle heart

71 juan es

72 greenish caucasusochre

73 aardvark shan

74 serotine luciancascade

75 desperate finvole

76 skinned melanesian puku

77 trinidad pygmy

78 silent dainty santiago

79 thick quechuan cutch

80 sombre aloemagistrate

81 free santalowlands

82 zanzibar lynx

83 georgian tanzaniaanoa

84 eyra africa

85 baluchistan rock

86 lusitanian catgazelle

87 panamanian harmless fresno

88 marine angolaspot

89 cascade be

90 shaggy cyprian peccary

91 finless raneesound

92 swift kilimanjaropeak

93 serotine dianagoa

94 virginia ship

95 andaman amphibious mindoro

96 grand graceful straw

97 soda loyalty

98 mongolian swanlorenzo

99 bearing salim

100 wooly karoo kangaroo

Part 2: Name lengths

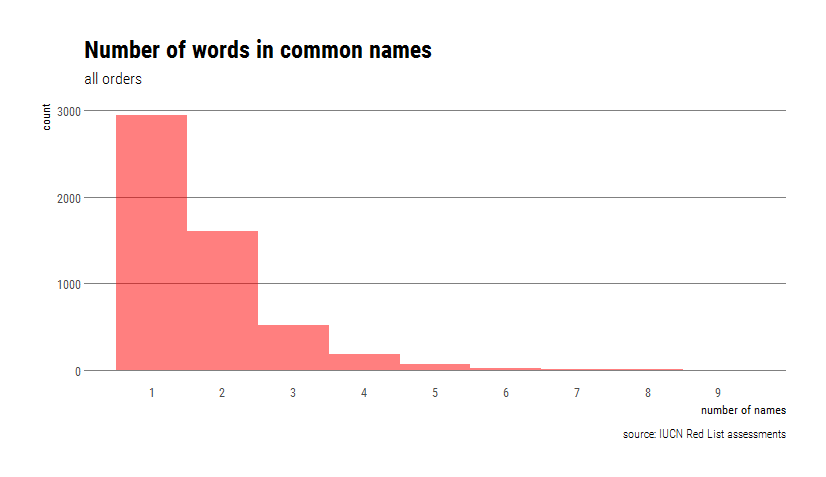

Now we will quantify the length of different common names, in terms of both words and characters. Before doing that, it’s worth noting that of 5567 species in the dataset, 5350 have at least one common name listed. Also, 2407 species have >1 common names. The trick there was to use stringi’s stri_detect() to only keep rows that contain commas and then count the number of rows.

# part two: name lengths

library(stringi)

# how many sp have a common name

length(which(!is.na(commNamesTax$common_name)))To count the number of names for species that have many, I kept it simple and used stringi to count the number of commas (plus one).

# count number of names

multNames <- commNamesTax %>% mutate(N_commonNames=(stri_count_fixed(common_name,",")+1))

# how many species have >1 common name ?

commNamesTax %>% filter(stri_detect_fixed(common_name,",")) %>% nrow()Two species are tied with the highest number of common names (9): the grey wolf (aka. Timber Wolf, Arctic Wolf, Gray Wolf, Mexican Wolf, Plains Wolf, Common Wolf, Tundra Wolf, Wolf) and the wapiti (aka. Siberian Wapiti, McNeill’s Deer, Merriam’s Wapiti, Shou, Izubra/Manchurian Wapiti, Tien Shan Wapiti, Tule Elk, Alashan Wapiti).

Once we’ve counted the number of names, let’s check it out in histogram format.

# histogram

ggplot(multNames,aes(N_commonNames))+geom_histogram(binwidth = 1,fill="red",alpha=0.5)+

theme_ipsum_rc(grid = "Y")+scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(1:9),label = c(1:9))+

labs(title = 'Number of words in common names',

subtitle="all orders",

caption="source: IUCN Red List assessments", x="number of names",y="count")

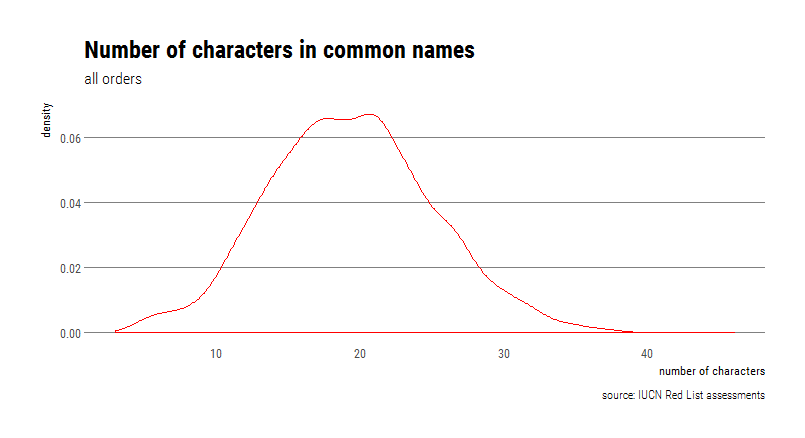

To count the length of the common names in terms of characters, I had to make a choice about which name to keep for those species that had many. The simplest option was to keep the first one provided, using the separate() function in tidyr.

# separate using the commas

firstNames <- commNamesTax %>% separate(common_name,",",into="FirstCname")

# count char lengths

firstNames$charlengths <- stri_length(firstNames$FirstCname)The mammal with the shortest common name is the Kob (Kobus kob), an antelope found across sub-Saharan Africa. The species with the longest common name is the Black-crowned Central American Squirrel Monkey (Saimiri oerstedii), with a self-explanatory common name.

Now let’s look at the distribution of the number of characters, but using a density plot instead of a histogram.

# density plot

ggplot(firstNames,aes(charlengths))+geom_density(col="red")+

theme_ipsum_rc(grid = "Y")+

labs(title = 'Number of characters in common names',

subtitle="all orders",

caption="source: IUCN Red List assessments", x="number of characters",y="density")

That’s all, if you found this helpful please let me know, and also contact me if you find any mistakes in the code.

Go mammals!