If you present will you publish?

We need publication rate analyses for ecology, evolution, and conservation conferences

The title for this post borrows part of the title from: Kanwalraj M. & S. Butterworth (2013) If You Present Will You Publish? An Analysis of Abstracts at the Craniofacial Society of Great Britain and Ireland Conferences 2000–2009. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal: Vol. 50, No. 6, pp. 713-716. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1597/12-335

In a previous post I summarized an analysis of the content presented at Mexican mammalogy conferences over a number of years. The paper in question mentioned a gap between what was presented at conferences with what is published in the literature. This got me interested in previous efforts to track the fates of studies presented at scientific conferences and their paths to publication.

While searching for these types of studies I stumbled upon Bibliometrics and Scientometrics, two closely related approaches to measuring scientific publications and science in general, respectively. These fields focus on networks of scholars and scholarly communication, the development of areas of knowledge over time, and the measurement of productivity and impact for scholars or publications (read more).

Analyses of publication rates are very common for medical and biomedical science conferences, but practically non-existent for important fields in life sciences such as ecology, evolution, or conservation. The conference to publication pathway (or bottleneck?) is an important issue to address, because we need to know:

- How much presented research is left unpublished and what it is about

- How long it usually takes for research behind a talk or poster to get published

- Which factors determine whether or not presented material gets published

- How trends in research on a particular topic correspond as represented by conference communications vs peer-reviewed literature

Understand publication rates can help increase diversity in science (for example: by identifying which demographics are underrepresented in the presentation-to-publication workflow and why). Data on publication rates can influence the way conferences are organized and documented, and define appropriate incentives for presenting research at scientific conferences. The scientific merit of some conferences is sometimes measured by tracking the subsequent publication of its presentations.

Even when modern conferences put on great workshops, career development sessions, social events, discussion groups and special symposia; it is reasonable to assume that high publication rates reflect favourably on a conference and its organizers. I don’t advocate for this at all, but conference organizers pushing for higher publication rates may want to reduce the number of abstracts accepted for presentation, or scrutinize abstracts closely and reject content that is not necessarily publication-oriented (vague preliminary results, location-specific reports, and commentary on broad topics or policy).

Why present

Scientific conferences are a great forum for discussion, networking, getting a sense of what the current state of research is, and ultimately becoming a part of the research community. In addition to gaining experience with public speaking, language skills, and presentation design; I was always told to present my work at conferences as a way to promote published or upcoming work, or to get feedback and new ideas from a wide pool of experts. *Note how I leave out how presenting can help with “getting noticed” even if it’s “half the battle.”

Why publish

Refereed journals are still the foundation of scientific communications. Scholarly publishing broadens the research base upon which a scientific discipline is built, and reflects individual or institutional research output, impact and productivity (whether we like it or not). Publications make the research presented at a conference more permanent and accessible to the scientific community. This way information isn’t lost and unnecessary replication can be avoided. Scholarly publications also include more detail and thorough references, and they have the added rigour of peer-review.

There have been recent changes in how we go about making conference communications more permanent and increase their reach beyond the people sitting in the same room. We can put slides online on distribution platforms like Figshare and Slideshare, talks get live-tweeted (when it is allowed), and in some cases live-streamed or filmed for public viewing.

Personally, only half of the projects I’ve ever presented at conferences are now published papers. In some cases I received important feedback that sent me back to revise the study design and get more data, in others I’m still struggling with the review process, and I admit that I dropped an old and unviable project that may not have been presentation-worthy to begin with. Wouldn’t it be cool to know these patterns for everyone else?

Publication rates

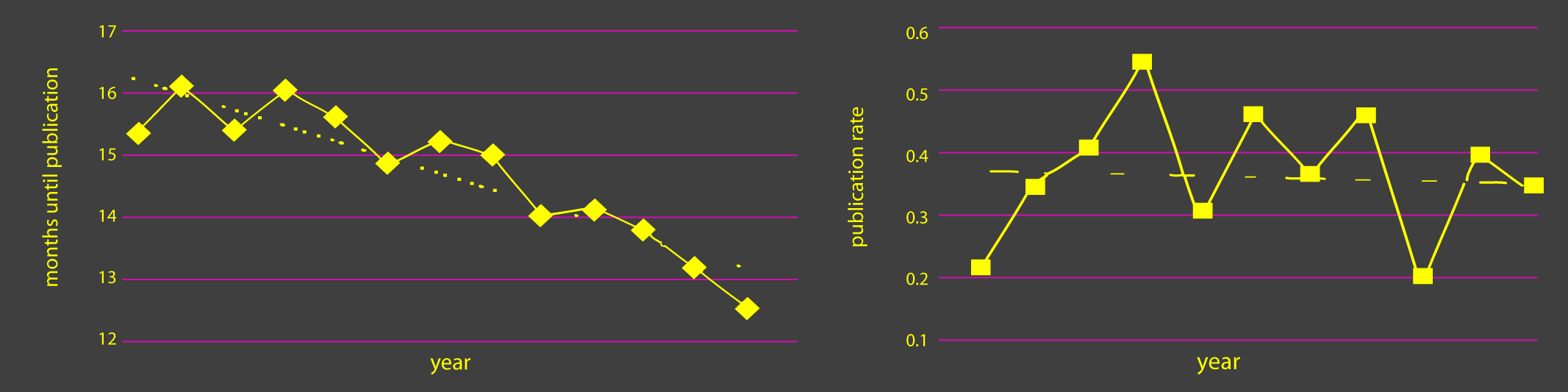

In very comprehensive review from 2008, Roberta Scherer, Patricia Langenberg, and Erik von Elm combined data from 79 reports of publication rates. These data represented 29,729 abstracts from at least 250 conferences in over 20 different disciplines (mostly biomedical). They found that 44.5% of conference communications were subsequently published in peer-reviewed journals, roughly 12 to 32 months after presentation.

The authors in this review identified some interesting factors associated with the publication of conference communications: oral presentations and those reporting ‘positive’ and ‘significant’ results had higher publication rates. Certain study designs (for clinical trials) were also associated with higher publication rates. An earlier report by roughly the same team also found that abstracts were more likely to be published subsequently if presented either orally, at small meetings, or at meetings held in the USA. Research in publication rates for biomedical science meetings has advanced to a point where a 2015 systematic review quantified the reasons for nonpublication of presented material. The main reason given by authors was lack of time. Other common reasons were: lack of resources, publication not an aim, low priority, incomplete study, and trouble with co-authors.

Medical and biomedical research (pathology, dental research, neuroradiology, pharmacology, etc.) is very different from ecology, evolution, or conservation - this is likely to affect the type of content presented at meetings, the nature of these meetings, and the resulting publication rates. Factors like funding sources, professional affiliations with varying expectations to publish, and direct implications for human health make publication rate analyses for biomedical research practically incomparable with other fields.

What’s missing?

I found more reports of publication rates published after 2008 to complement the Scherer et al. review, but only one focused on scientific meetings relevant to ecology, evolution, or conservation, bringing the grand total to … two.

Bird and Bird (1999) analysed 425 abstracts randomly selected from 849 presented at the 1989 and 1991 meetings for the Society for Marine Mammals, reporting that peer-reviewed publications resulted from 55% of presentations. A less outdated and very nice paper from 2014 by Jon McRoberts and colleagues examined presentations at annual meetings organized by The Wildlife Society (TWS) between 1994 and 2006. Of the 6,279 presentations given at TWS annual conferences, 28.2% resulted in publications. The mean time between presentation and publication was 30 months, and the authors were able to determine that 87.9% of published communications came out after being presented at conferences and not before. This is a promising start, but we still need to know the publication rates for other relevant scientific conferences and to identify the factors associated with presented content that ultimately becomes part of the knowledge base.

Lots of questions

After figuring out publication rates, we can dig deeper and start addressing other interesting issues related to the presentation -> publication pathway. The questions and hypotheses below are just a few examples that I came up with from (possibly biased and/or unrepresentative) personal experience.

Are presentations by senior researchers more likely to become publications?

Senior researchers may present material that is already published, or they may be more likely to eventually publish their presented material. On the other hand, senior academics might be giving broad talks about multiple projects in their lab or giving commentary presentations which may not represent unique publications identifiable by bibliometric methods that depend on titles, authors, abstracts, and key words.

Are non-academic presenters underrepresented in published literature?

Conservation conferences often feature participation by NGOs, citizen scientists, and government entities. These attendees sometimes report their research internally without leaving a published record of whatever content they present, and these gaps could end up affecting conservation practice.

Is material presented at conferences more likely to be published when there is no language barrier to contend with?

Attendees that are not native speakers may be presenting in English at large international meetings and then publishing their work in other languages that are usually excluded from bibliometric analyses (and outside of the ‘top’ journals in their particular field).

Are certain topics within a conference more likely to be published?

For large and heterogeneous conferences, publication rates may vary between presentations on trendy topics with charismatic study groups in relation to basic research on non-charismatic groups or theoretical methods papers.

…

This list could go on and on, but it’s evident that we need analyses of content and publication rates for scientific meetings about zoology, ecology, evolution, conservation, marine science, etc…

What next?

Because there are essentially no publication rates analyses for any conference in my particular field, any large meeting represents a good start. Large international meetings (I’m thinking INTECOL or ICCB) may be interesting options, and the 30 month period between presentation and publication (from the McRoberts report) provides a time reference to start evaluating conference data as recent as 2012.

The methods are already out there and the analyses are straight forward. New approaches such as text mining and web scraping can make things easier, along with the cooperation of the societies and committees in charge of organizing conferences. One could also poll attendees at future conferences on whether or not the work they are presenting is published, submitted, or intended for publication. Special interest groups, local chapters, or student sections of various organizations that put together periodic conferences should start looking into publication rates.

If anyone reading this is interested in publication rates and willing to pursue an analysis for any pertinent meeting, please let me know. If I somehow left out a relevant study also let me know.