Extinction risk research in mammals

My latest paper was recently published online, and I hadn’t been able to post about it until now. The link is here, and here’s a copy of the Early View version.

Applications of the comparative method to conservation science really took off in the past 20 years. Research on extinction risk has benefited from several elements coming together, such as phylogenies with good taxonomic coverage, comprehensive datasets of species biology, and the IUCN Red List conservation assessments. Most extinction risk research has focused on animals, and especially the well-known vertebrate classes: mammals and birds. This paper looked at what we have been researching compared to what we should be researching, focusing only on multispecies extinction risk studies. I reviewed 68 studies and quantified their scope, sample sizes, variables, and various details describing the methods used in each one.

The taxonomic and geographic biases of mammal research in general apply to extinction risk research. Everyone prefers primates and carnivores, but some orders of small mammals (rodents and Eulipotyphla) urgently need more research specifically aimed at identifying what puts some species at risk while others are doing OK. Fortunately, the IUCN Small Mammal Specialist Group is already on it.

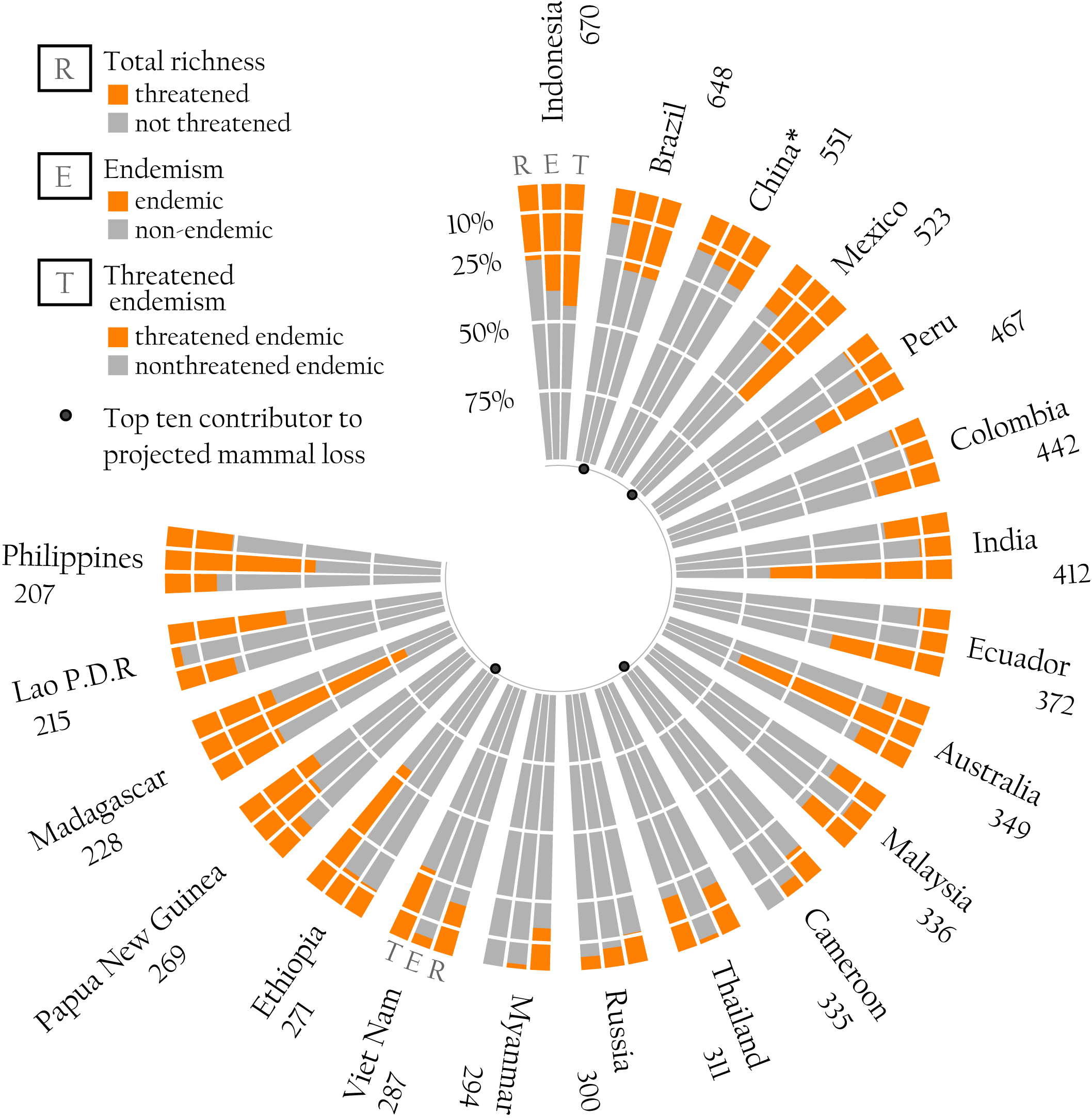

Spatially, most countries and bioregions rich in endemic and threatened mammals are understudied. For example, I put country-level threat, diversity, and endemism into the figure below. This is nothing revolutionary, but out of these 20 relevant countries: only India and Australia have dedicated studies. Christophe Ladroue is the real MVP for his Polar Histogram function, check it out here.

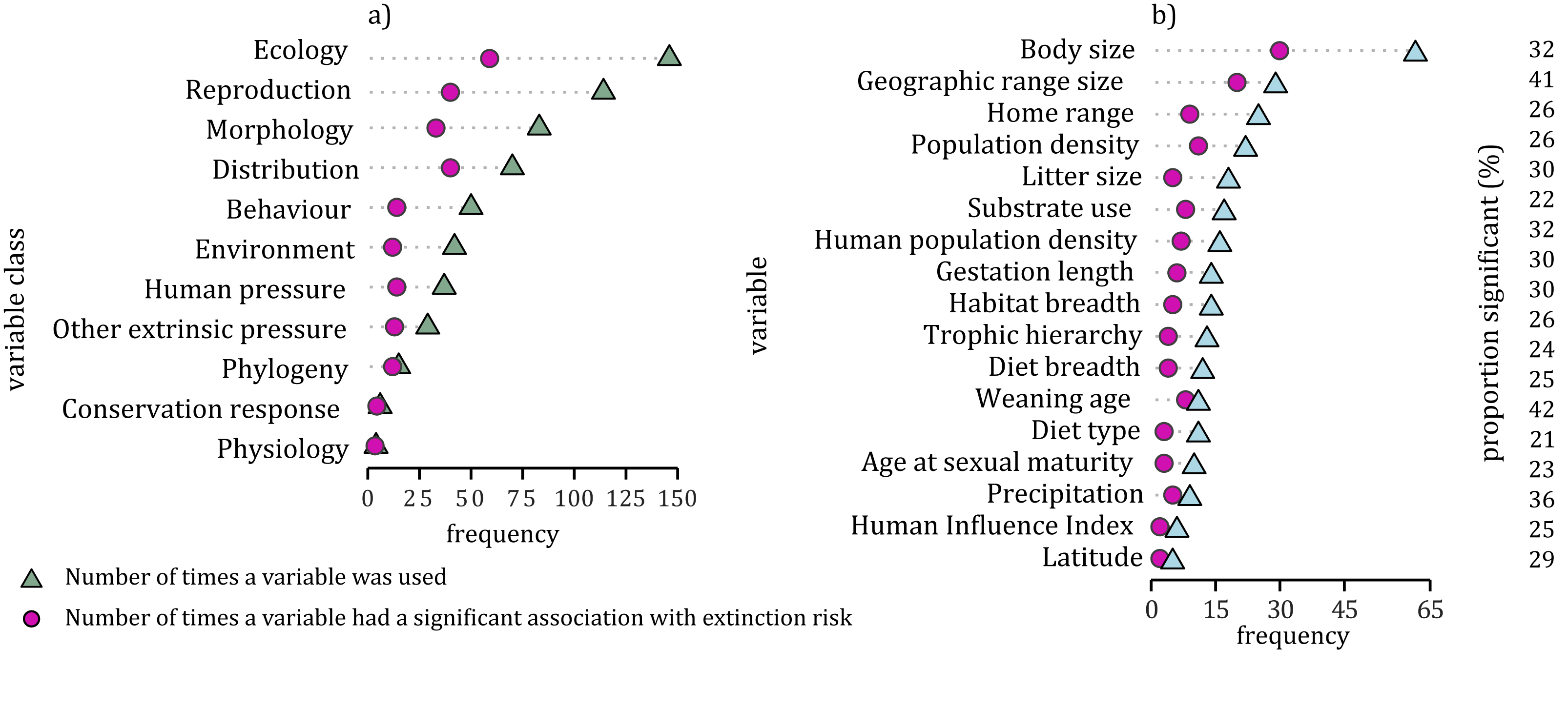

The paper also comes with a comprehensive database of all the variables that have been used to try and predict extinction risk in mammals. Overall, body size was the most popular variable, used in virtually all studies, followed by geographic range – used in half of the studies. These two popular variables are decent predictors of threat status, but this might just be because they are used so often. The exciting results came when I looked at how often different variables had significant associations with extinction risk in proportion to how often they were used (Figure below). Proportionally: weaning age, geographic range, and precipitation were the most consistent predictors, they showed significant associations with extinction risk in almost half of the studies that included them. In this proportional approach, body size had significant effects on extinction risk in only a third of the studies that included it. We should start focusing on weaning age and what it means in relation to the pressures that put species at risk in the first place.

With my results, I suggested Southeast Asia and the Caribbean as urgent and interesting areas for future study. They both have unique mammal faunas, lots of endemics, high threat, and many recent extinctions. I also give some methods suggestions based on the patterns I saw across all the studies. These suggestions boil down to one message: avoid unnecessarily degraded datasets. Authors often drop species with incomplete data, or make little effort to ensure overlap between the species in comparative datasets and those that appear in published phylogenies (a key component in most approaches).

Writing a single-author paper

I’ve been fortunate in all the collaborations I worked on. I never had co-authors stalling a paper, or any major disagreements in how things should be done. This is the first time I’ve written and published a paper by myself, and a single-author paper was somewhat of a challenge.

Without any pressure to provide progress to co-authors, writer’s block was an issue I had to just put aside and push through. I had to work on all parts of the paper, some of which normally get divided between co-authors to leverage their expertise. With less eyes on the manuscript, typos and minor errors were more likely to leak through onto final versions so I had to be extra careful in the proofreading. When it was time to address reviewer comments I really noticed the importance of having collaborators. I’ve always worked with people with vast experience in publishing research, and this showed when they would know how to navigate the review process. At this point I’m still learning to balance when to appease reviewers or editors and when to stand strong with a particular method or viewpoint.

I’ve heard that there can be significant career value is writing a single author paper, particularly for grad students and postdocs. It shows independence, and that one is not completely dependent on senior people for ideas, guidance, or techniques. That was not exactly my motivation for this paper, but I hope it looks good on my CV. If anyone wants the code for recreating the figures in this paper just let me know.